Purchase the Chōkaku Today!

For only $899.99, alter your reality with the new OpenAI Chōkaku™ Audio system. This system features embedded ChatGPT® 7o technology, full spatial audio, and our latest Z8 chipset to create your perfect audio world. Compatable with the Shiya Pro Max, Shiya Pro Max Super, and Shiya Pro Max Ultra models, your future is only one click away.

For a limited time only, enable user telemetry for up to 20% off!*

* Restrictions may apply.About This Project

"Language-translation technology has developed to the point where people have lost all need to learn foreign languages. AI-powered translations can closely approximate meaning across languages, but how will this affect interpersonal relationships, the impact on the culture of language, and the global value of unique culture?"

The Chōkaku Project was driven by the question above; I wanted to explore the impact of technology on language learning and the ongoing issue of language death. I explored this topic through the lens of the development of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality interfaces, constructing the narrative of the potential degredation of interpersonal relationships as a result of technological "innovation".

Research

Machine Translation

The history of Machine Translation is long and complex, but, perhaps to the detriment of veracity, I would simplify it to 4 major developments:

RBMT (Rule Based Machine Translation)

Introduced in the 1950s, RBMT is the use of manually written "rule-based" dictionaries to perform the translation of one language directly to another.1

EBMT (Example Based Machine Translation)

Introduced in the 1980s, EBMT is the use of "similar sentence pairs" to directly correlate comparable sentence structures.1

SMT (Statistical Machine Translation)

Introduced in the 1990s, SMT creates computational probabilities of accurate translation through the use of large bilingual language databases.1

NMT (Neural Machine Translation)

Introduced in the 2010s, NMT utilizes machine learning to create encoders and decoders; the input sentence is encoded into a series of vectors, which are then mapped to a decoder that translates to the output language.1, 2

These forms together create the basis of all computational translation. If we consider language, however, as a product of culture, can we really directly translate one sentence to another merely as a series of vectors?

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity3 posits that our worldview is largely shaped by our language; linguistic differences in concepts like space, color, and action can radically alter our perception of reality. One may argue that these cultural differences can be reduced to a series of inputs through the Classical Computational Theory of Mind (CCTM).4 However, to reduce culture and perception to a series of inputs and outputs ignores the complexities that underly not only broader culture, but the personal experiences of every individual that forms its component parts. In this sense, to participate in language is not to translate or transform one language input to one output, but rather to reform one's perceptions of the world and become an active participant in its corresponding culture.

Language Death

The primary issue this work seeks to address is that of language death. According to UNESCO, "[M]embers of ethnolinguistic minorities are increasingly abandoning their native language in favour of another language", 5 which, as scholars have posited, could result in the average rate of language death being "one language lost per month"6 in as little as 40 years. Although there are a variety of factors contributing to this issue, UNESCO has stated that it is largely caused by a deficiency in the following 8 attributes within a culture:

- Intergenerational Language Transmission

- Absolute Number of Speakers

- Proportion of Speakers within the Total Population Trends in Existing Language Domains

- Response to New Domains and Media

- Materials for Language Education and Literacy

- Governmental and Institutional Language Attitudes and Policies, Including Official Status and Use

- Community Members' Attitudes toward Their Own Language

- Amount and Quality of Documentation 5

I would argue that the rapid development of language translation technology could potentially result in a decrease of intergenerational language translation, reducing the absolute number of speakers. In addition, with the ongoing globalization of English as the de facto lingua franca, a lack of compulsion in language education could result in furthering the lack of language diversity in favor of dominant global language universality.

Development

As a premise, I considered the possibility of a company like OpenAI entering the consumer hardware space, developing Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality interfaces as an extension of their Artificial Intelligence products. Largely what Computationalists see as the primary difference between man and machine is our interface with the world: our viscera, our sensory capabilities. As such, I imagined a world where our companies like OpenAI would seek to replace these sensory apparatuses, incentivized by capitalist gain through control over the senses of the populus. For this, I developed two primary products, the Chōkaku, derived from the Japanese word 聴覚 roughly meaning "auditory perception", and the Shiya, derived from the Japanese word 視野 roughly meaning "view" or "perspective".

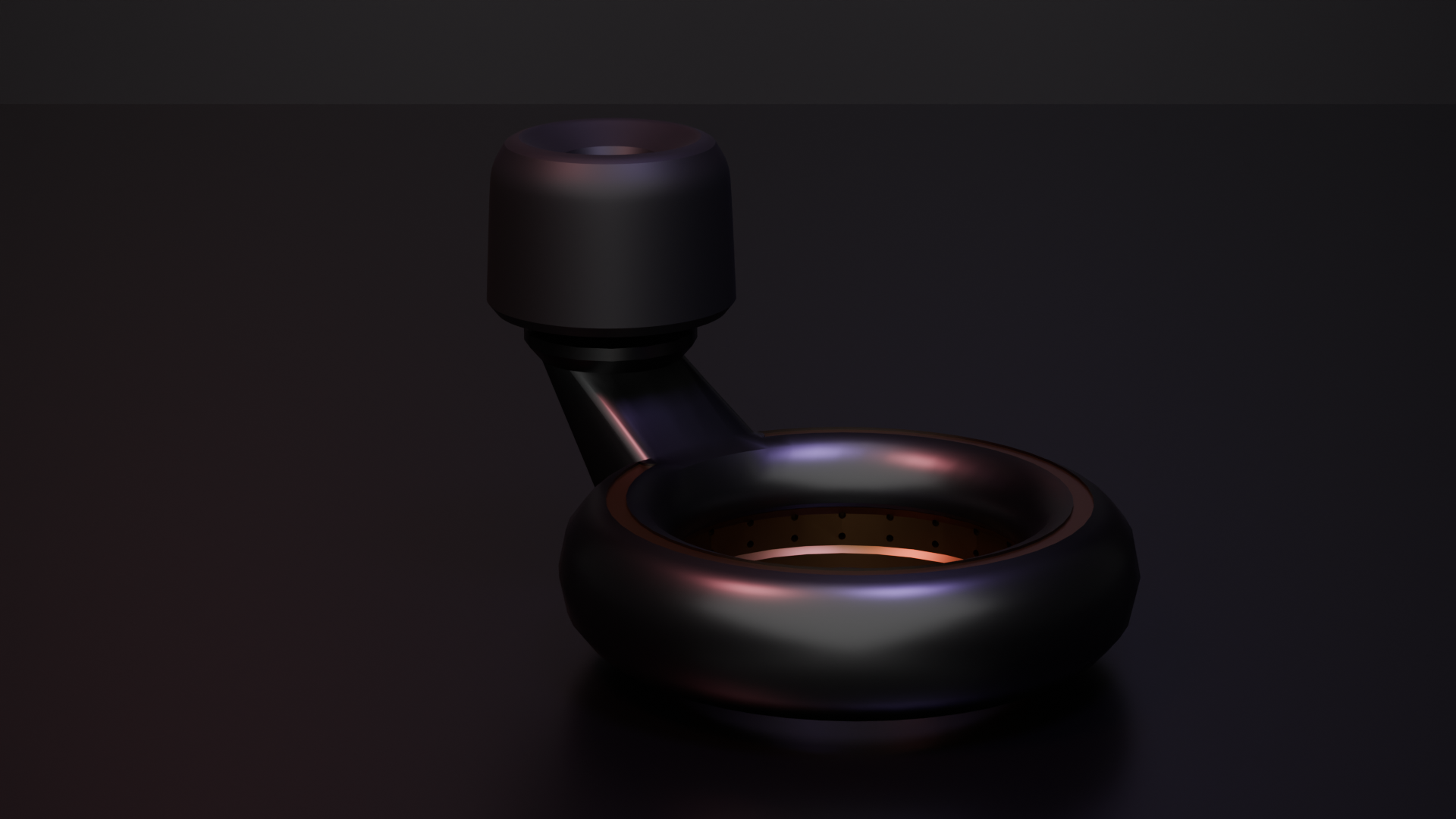

Chōkaku

The Chōkaku product was designed primarily as a replacement interface for user's auditory perceptions. It serves both as the interface through with to experience reality, and an interface for the "second mind", Artificial Intelligence directly connected to everyday life. Of course, the design tendencies of the future cannot be accurately rendered through the purview of the present; I instead sought to emulate the paragon of modernity OpenAI currently seeks to portray itself as.

Shiya

As a subsidiary element to this project, I developed the Shiya AR/VR Glasses. In a similar fashion to the Chōkaku, these serve as a replacement for the user's visual perceptions, as well as incorporating the same "second mind" Artificial Intelligence. They serve to digitally reconstruct the world, acting as an interface through which users can traverse physical reality.

Scene

Set 20 years in the future, the scene represents a digital reconstruction of a standard domestic household, the house of the protagonist's grandfather. The scene is viewed entirely through the Shiya's lens, and demonstrates a disconnect between our physical reality and what is digitally replicated.

Narrative

Through these elements, I built the narrative of the protagonist's interaction with his grandfather through the form of a testimonial video. The grandfather, speaking only Scottish Gaelic, communicates with the protagonist, yet his speech is constantly impeded by the English translation provided by the Chōkaku. This narrative begs the question, could technology degrade our interpersonal relationships? Furthermore, by the means of this technology, if the protagonist no longer feels it necessary to learn a dying language like Scottish Gaelic, could this technology be a factor in the death of this language? And who is responsible if it does?

Works Cited

1

Wang, H., Wu, H., He, Z., Huang, L., & Church, K. W. (2022). Progress in Machine Translation. Engineering, 18, 143-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.03.023

2

Mohamed, S. A., Elsayed, A. A., Hassan, Y. F., & Abdou, M. A. (2021). Neural machine translation: Past, present, and future. Neural Computing and Applications, 33(23), 15919-15931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06268-0

3

Ottenheimer, H. (2009). Language and Culture. In The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology (3rd ed., pp. 18-46). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

4

Rescorla, M. (2024). The Computational Theory of Mind. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2024). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/computational-mind/

5

UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. (2003). Language Vitality and Endangerment. International Expert Meeting on UNESCO Programme Safeguarding of Endangered Languages. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/00120-EN.pdf

6

Bromham, L., Dinnage, R., Skirgård, H., Ritchie, A., Cardillo, M., Meakins, F., Greenhill, S., & Hua, X. (2022). Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 6(2), 163-173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01604-y